F. Scott Fitzgerald thought his fellow writer and (sometimes) friend Ernest Hemingway possessed the most dynamic personality in the world and “always longed to absorb into himself some of the qualities that made Ernest attractive.”

Other friends and observers of Hemingway remarked on the “strange power of his presence,” his “poise and strength,” and a “pervasive and inescapable force of personality” that registered as “so vast, so virile.” As his first wife remarked, he left “folks falling into fits of admiration.”

As a young man, older men looked up to him; as an older man, men and women of all ages called him “Papa.” Those in Hemingway’s orbit, writes his biographer Carlos Baker, “were not only content but even eager to tan themselves like sunbathers in the rays he generated.”

What accounts for this magnetic allure, this larger-than-life charisma that allowed Hemingway to get away with plenty of bad behavior and continues even today to make him incredibly compelling despite his considerable flaws?

Part of it was the way he evinced an undiluted, unapologetic masculinity — a constellation of qualities which included originality and independence, stoical fortitude and purpose, and a primordial vigor and strength. He was a man with an indomitable pride, who described himself as being “without any ambition, except to be champion of the world.”

Part of it was his considerable charm — the way he listened to what someone was saying with an intense, flattering focus, and spoke to them “in that special way of his that made the words come to you through a corridor of intimacy”; as one mentee remembered, he “always appear[ed] to be sharing a secret.”

Part of it was his zest for life; his twinkling eyes that were ever on the lookout for the next great adventure; the ready smile and laugh that said to his companions, “Let’s have a hell of a good time together.”

And, part of it was the sheer vastness of his skills and aptitudes — the seemingly limitless number of things he could do, and did.

Hemingway is in fact one of the very best examples of a concept we explored a few years ago: being a “T-shaped” man.

I’m not talking about being T-shaped physically (though that’s desirable too), but in the way your skill sets are structured.

A T-shaped man has two characteristics: First, he has an interest in and competent grasp of a broad range of aptitudes, skills, and know-how. This characteristic is represented by the horizontal stroke of the T. Second, he has a focused expertise in one particular skill or discipline. This characteristic is represented by the vertical stroke of the T. In short, a T-shaped man possesses both breadth and depth; he is a jack-of-all-trades, and, a master of one.

Being T-shaped allows a man to develop confidence, experience more of life, gain power, and leave his mark on the world, and, it’s a model Ernest Hemingway fit to a, well, T.

Today we’ll take an inspiring look at how Hemingway developed both the horizontal and vertical axes of the T-shaped life in order to do more, see more, and be more than 99% of the human population.

Note: Some people feel that because Ernest Hemingway committed suicide, he shouldn’t serve in any way as an example of how to live one’s life. But the reasons for his suicide are much more complicated than most understand, and it was not something he did casually or cavalierly. I’ve written up a note here for those who wish to learn more.

THE T-SHAPED LIFE OF ERNEST HEMINGWAY

“He was proud of his manhood, his literary and athletic skills, his staying and recuperative powers, his reputation, his capacity for drink, his prowess as fisherman and wing shot, his earnings, his self-reliance, his wit, his poetry, his medical and military knowledge, his skill in map reading, navigation, and the sizing up of terrain.” —Carlos Baker, Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story

“He told me how to use one’s built-in shit detector, how to enjoy idle time, when to be aggressive, when to give ground, how to set your hook on a hit from a sailfish, how to swing your shotgun to transect the flight of a pheasant, how to evaluate a racehorse during the paddock parade.” —A. E. Hotchner, Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir

Breadth of Knowledge/Competence

In his own time, some critics thought Hemingway engaged in “he-mannish posturing” — that the whole man’s man thing was something of an act. Today we’re even more apt to see him as a caricature of masculinity and wonder if photos showing him doing manly things were more carefully staged photo-ops — akin to Vladimir Putin riding shirtless on horseback — than accurate reflections of how Papa really spent his time.

But if authenticity is judged by the correspondence between what one talks about and what one does — between words and action — then Hemingway was as real as they come. He in fact hated posers, the non-producers of the world — those who, like the dilettantes who loitered in Paris cafes, fancying themselves as artists, but never putting in the work it would take to become such, failed to follow through on what they said.

Papa was not of this breed.

He did far more things than cameras ever captured (and to which journalists were never invited; publicity literally made him sick), tried never to write fiction about things he hadn’t experienced in fact, and began his education in what would become beloved lifelong pastimes long before there existed a wider stage on which to perform.

With an enduring curiosity, penchant for autodidactic education, and keen powers of observation, Hemingway became both a man of words and a man of action, and gained real, earned competence in a variety of areas:

Outdoor Skills

Ernest’s education into the world of manly skills began nearly as soon as he left the womb. Though the family lived in a nice suburb of Chicago, and his father was a doctor, the Hemingway patriarch was also a thoroughgoing outdoorsman who wanted to raise his children to be as competent in the woods as on the city streets.

Hemingway’s father founded a nature-study group in the area, which Ernest joined in kindergarten. Happily tagging along with older boys, he passed afternoons and weekends birding and collecting specimens, which he then spent hours examining under a microscope given to him by his grandfather on his fifth birthday. Even as a toddler, his mother remembered, Ernest was “a natural scientist, loving everything in the way of bugs, stones, shells, birds, animals, insects, and blossoms.”

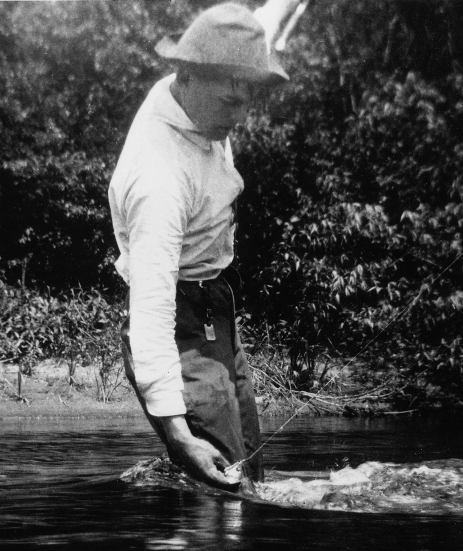

Learning how to capture bigger game constituted a significant portion of young Ernest’s outdoor education. By the time he was two and a half, his father had taught him the rudiments of shooting a gun, and by the time he was four, he could handle a pistol. When the boy was three, his father took him fishing for the first time, and a year later, he could spend all day casting line from a row boat, under the downpour of constant rain, without complaint. Hemingway’s angling instincts and marksmanship improved as he got older and continued to practice; his father would give him only three shotgun shells for an entire day of hunting, forcing him to always be sure of his shot.

Hemingway Sr. further instructed his son on how to cook wild game, as he insisted that Ernest consume whatever he killed. This rule would develop in Ernest a taste for squirrel, possum, raccoon, pheasant, duck, quail, partridge, doves, and all kinds of fish, though initially it got the boy into a spot of trouble; at age three, he shot a porcupine, and though Ernest boiled it for hours, it never got any less tough or more edible, and he had to choke down every last bite. Though in later life Hemingway sometimes shot more game than he could eat (which made him feel ashamed), he very often stuck to his father’s principle, frying up cornmeal-covered trout over a fire, living on elk and venison while taking week-long pack trips in the mountains, downing greasy, gamey, nearly rare bear steaks his fellow companions found disgusting, and even eating lion meat on an African safari that couldn’t have been any more raw — he literally cut it away from the spine of a just-downed cat and popped it in his mouth.

Hemingway’s father, Baker reports, imparted to him a great many other things regarding “a knowledge and love of nature”:

“He taught Ernest how to build fires and cook in the open, how to use an ax to make woodland shelter of hemlock boughs, how to tie wet and dry flies, how to make bullets in a mold that Anson [his grandfather] had brought back from the Civil War, how to prepare birds and small animals for mounting . . . He insisted on proper handling and careful preservation of guns, rods, and tackle, and taught his son the rudiments of physical courage and endurance.”

As a result of this tutelage, Ernest “shared his father’s determination to do things ‘properly’ (a favorite adverb in both their vocabularies),” and was able to handle outdoor adventures on his own at a young age.

His family owned a cottage on Walloon Lake, Michigan, and at age fourteen, Hemingway pitched a tent on some nearby land and slept in it the entire summer, sometimes slipping out at night to go canoeing under the moon.

At age fifteen he and a friend camped at a farm by the lake, and spent the summer gathering hay, working the fields, and milking the cows, and then used a boat to sell produce to cottages along the shoreline.

At age sixteen, he and a buddy took a weeks-long backpacking trip, hiking (and sometimes hopping a train), between towns, fishing a river each day for their sustenance, and sleeping along its banks each night. His friend left halfway through the trek, and Ernest continued his explorations alone.

Hemingway’s love for the outdoors, his preference for wild places over big cities, would continue throughout his life. In the woods and mountains he felt recalibrated, renewed, re-enlivened, and his prowess with gun and reel only grew with time. He always aimed to kill rather than wound, and more often than not, found his mark. He could take down a black bear in a single shot, catch over a hundred trout a month in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming, hook a world-record-size marlin, shoot a large bull elk, on the run, through the lungs, at a hundred yards, and face down a grizzly standing on its hind legs. Said a companion who was astonished at Hemingway’s skill: “I saw Ernest jump from his horse, cover a hundred-yard dash on foot, and drop a running antelope at two hundred and seventy-five yards. That’s rifle shooting, if you ask me.”

Hemingway pursued game for sport, and for food, and sometimes even for survival; when supplies ran low amongst the troops he was reporting on during the Spanish Civil War, he went hunting along the front and returned with ample game for the hungry and appreciative men.

Tactical Skills

Even though Hemingway never served officially in the military, he still managed to win the Italian Silver Medal of Valor and the US Bronze Star, and carried himself on the battlefront with such confidence that he was sometimes mistaken for a four-star general by enlisted men.

Kept out of military service in WWI because of a bum eye, Ernest volunteered at age eighteen to drive ambulances in Italy. His stint as an aid worker was cut short, however, when he was hit while bringing chocolate and cigarettes to Italian soldiers on the front. An exploding mortar shell embedded 227 metal fragments in his body, but Hemingway, seeing a soldier seemingly more wounded than he, threw the man over his shoulder and fireman-carried him to a medical post. Along the way, he was hit again, this time with two machine gun bullets to the leg. Yet he kept staggering forward and delivered the soldier to safety. It was for this action that the Italians presented Hemingway with the Silver Medal.

Short as his medical service was, Hemingway still picked up some basic first aid skills that he would use throughout his life. Once while covering the war in Spain, a car he and his companions were following crashed into a ditch; Hemingway was the first to rush over to the victims and administer aid. Later in life, when his wife was dying from complications of an ectopic pregnancy, and her doctor told Hemingway that all hope was lost, Papa donned a surgical gown and mask himself and started a line of plasma into her vein, saving her life. Hem was, she said with understatement, “A good man to have around in times of trouble.”

At the beginning of WWII, Hemingway volunteered a very different set of services, getting permission from the U.S. ambassador to Cuba to start a counterintelligence organization designed to thwart the infiltration of the island by Nazi fifth columnists. He recruited a broad spectrum of fellow amateur agents, including jai alai players, a Catholic priest, waiters, fishermen, Spanish nobles living in voluntary exile, and an assortment of bums who hung out on the wharf. Ernest’s network of Spanish-speaking spies sent him reports, which he then translated and passed on to the American embassy.

Wanting to get more in on the action, Hemingway then struck on the idea of furnishing his 38-foot fishing boat, the Pilar, with bazookas, grenades, short-fuse bombs, and .50-caliber machine guns, and using it to patrol the Cuban coast for Nazi submarines. He amazingly managed to finagle the desired arms and equipment from the Chief of Naval Intelligence for Central America, and Ernest and his hand-picked eight-man crew spent months running drills and scouting the waters. Much to Papa’s consternation, however, they only once spotted a U-boat, and it was too far in the distance to be confronted.

Hemingway then jumped over to the European front of the war as a correspondent embedded with the Army’s 22nd Infantry Regiment as it moved towards Paris by way of Normandy, Luxembourg, and the Hürtgen Forest.

Ernest understood well the nature of manly camaraderie, and how to contribute to it, and was thus accepted into the regiment’s ranks as much as any member of the military.

The enlisted soldiers looked up to him (sometimes mistaking him for a member of the brass), and respected his willingness to share in the hardships and hazards with the men — positioning himself, by choice, in forward combat positions, sleeping on the ground and in barns, getting by for weeks on less than four hours of sleep a night.

The officers respected him for this, as well as for the head he had for tactical matters. As Baker reports, the commander of the regiment, Colonel Buck Lanham, “was surprised at the speed and astuteness with which Hemingway absorbed military information. He seemed to have a built-in battle sense, and an almost professional instinct for terrain. His questions were intelligent.” The colonel found him to be a “real expert” in military affairs, “especially in regard to guerrilla activities and to intelligence recollection. . . . He had a true scout’s instinct.”

In referencing a knack for “guerrilla activities,” the colonel was not speaking in the abstract; during the war, Hemingway did not content himself with penning dispatches for the papers back home, but instead took a participatory role in the action. In violation of the Geneva Convention, which bars journalists from taking up arms, he stockpiled grenades, mines, and tommy guns, and led a band of French Resistance fighters on scouting patrols.

One of Hemingway’s greatest tactical aptitudes wasn’t one we typically think of as a skill, but can in fact be developed like any other: courage.

The professional soldiers were a bit in awe of Hemingway’s preternatural calm under fire. As a child, Ernest’s mantra was “Fraid of nothing!” and while as an adult he encountered situations that elicited great fear, he came to think of the feeling as cathartic and learned to control it to an almost unthinkable degree. Col. Lanham, who considered him “without exception the most courageous man I have ever known,” remembered a time he, Hemingway, and some fellow officers were having dinner in an abandoned house when a shell came ripping through one wall and out the other:

“In a matter of seconds my well-trained people has disappeared into a small potato cellar . . . I was the last one to get to the head of the stairs. I looked back. Hemingway was sitting there quietly, cutting his meat. I called to him to get his ass out of there into the cellar. He refused. I went back and we argued. Another shell came through the wall. He continued to eat. We renewed the argument. He would not budge. I sat down. Another shell went through the wall . . . We argued about the whole thing but . . . He reverted to his favorite theory that you were as safe in one place as another under artillery fire unless you were being shot at personally.”

Though Ernest was in some ways fearless, he wasn’t reckless; said another officer:

“He never admired raw courage, unless it was the only way of getting the job done. I never saw him act foolishly in combat. He understood war and man’s part in it to a better degree than most people ever will. He had an excellent sense of the situation. While wanting to contribute, he knew very well when to proceed and when it was best to wait awhile.”

After the war, Hemingway was awarded the Bronze Star for his bravery in reporting “under fire in combat areas.” The citation read: “through his talent of expression, Mr. Hemingway enabled readers to obtain a vivid picture of the difficulties and triumphs of the front-line soldier.” He could paint such a rich picture, because he had lived it firsthand.

Physical Aptitude

“He was massive. Not in height, for he was only an inch over six feet, nor in weight, but in impact. Most of his two hundred pounds was concentrated above his waist: he had square heavy shoulders, long hugely muscled arms (the left one jaggedly scarred and a bit misshapen at the elbow), a deep chest, a belly-rise but no hips or thighs. Something played off him—he was intense, electrokinetic, but in control, a race horse reined in.” —Carlos Baker

Hemingway was a man of big appetites — for life generally, and for food and drink specifically. Fortunately, he also had a big appetite for exercise, and whenever his body got too flabby (his standard was how a gun felt when you hefted it: “If it’s heavy, you’re out of condition. When it’s light, you’re in shape”), he pushed himself to lose the weight.

His love of physical activity began in his youth. As Baker explains, “Nothing pleased him more than working up a good swingeing [punishing] sweat: he and his father both believed that it learned the brain and cleansed the body.”

As a young man he participated on the school football and swim teams, and was always up for amateur games and romps. At age fifteen, he hiked 32 miles one Saturday with the local boys hiking club, and took a 25-mile jaunt the next week.

When he got older he continued to enjoy swimming, walking, and hiking, and also took up skiing and tennis. His regular pastime of big game fishing also gave him quite a workout; a tug-of-war with a 500+ pound tuna could last for seven taxing, buckets-of-sweat-producing hours. Fishing wasn’t a sedentary pastime for Hemingway, but a real battle.

One of his favorite ways of staying in literal fighting shape was boxing, a sport he had taken up in his teen years and continued to dabble in all his life. When he was living and writing in Paris as a twentysomething, he made money on the side by sparring with professional heavyweights. He loved to ask his friends and associates to face off against him too, and sparred with Ezra Pound and other fellow writers in his apartment.

Hemingway would box bare-fisted or with gloves, and accept all comers. When he lived in the Bahamas, he offered $250 to any native islander who could last three rounds with him, and he reportedly never had to pay up. As Baker writes, Hemingway was even up for bouts he hadn’t seen coming; when a young man from the States arrived unannounced at the front door of his Cuban home spoiling to fight, “Ernest angrily threw a dozen hard left hooks at his head and face. The young man fell bleeding. Ernest paid the cab driver and told him to deliver the boy to one of the small whorehouse hotels in Havana and wash him up.”

It wasn’t just the big physical movements that Hemingway joyed in, but the small ones too — all the little things that add up to “flow”:

“The things that please me are very simple things. Most of them seem to have to do with natural reflexes and co-ordination. Like things that happen so quickly in trout-fishing, correcting a cast already started in the hundredth part of a second in the air. When I was a kid every time I would do that I would be pleased. Now shooting and all the things that are made up of so many things to do and think at once all surrounding one central necessity please me.”

As Baker explains in describing a day-in-the-life, Ernest ultimately believed that “The first great gift for a man is to be healthy,” because staying healthy allowed him to do all the things — both physical and mental — that he loved:

“On the 19th he . . . finished thatching the pool shelter, sorted books for a new book case, swam ten laps, did seventy-five lifting exercises, shot a match with Alavrito Villamayor . . . and concluded the day with three sets of tennis and a few more laps in the pool. Such a program was necessary, as he told Mary, in order to write ‘good,’ love and cherish his new wife, think straight, fight when necessary, and enjoy ‘truly’ and with all five senses his one and only life while he was still able to love it. Once in condition, he would get back in the swing of writing.”

Indeed, as the man himself warned, “Fattening of the body can lead to fattening of the mind.”

Cultural Know-How

Even though many of Hemingway’s competencies centered on concrete, physical skills, and his lifelong desire to test and prove his toughness and endurance, he was hardly a dumb brute.

In addition to being able to wax poetic on boxing, weapons, and the nature of true courage, Hemingway could talk eruditely about the differences between the styles of great painters (his favorite by far was Cézanne), the nuances of various wines, and the history of villages and historical sites.

He was of course a world traveler; as Baker reports, in 1923 alone, a 24-year-old Hemingway “traveled some ten thousand miles–six times between Paris and Switzerland, three times to Italy, to Constantinople and back, once to the Black Forest, once down the Rhine.” His globe-hopping ways would continue as he got older, traveling twice to Africa, returning again and again to Europe, and of course developing a particular love affair with Spain. Over the course of his life, Hemingway not only visited but took up extended residences in Paris, Key West, and Cuba. As he did not like to visit or write about any place without being able to speak the language, he became fluent in Spanish, and could speak a passable Italian, German, and French.

Whether he was settled in one place or traveling abroad, Hemingway was a voracious reader. At any given time, he was typically reading four different books (a number that could sometimes swell to as many as ten), and consumed about a book and a half every day. Over the course of his life, Hemingway thus read thousands of tomes, on a wide variety of subjects, and, possessed of a keen memory, readily retained whatever he consumed.

Mastery

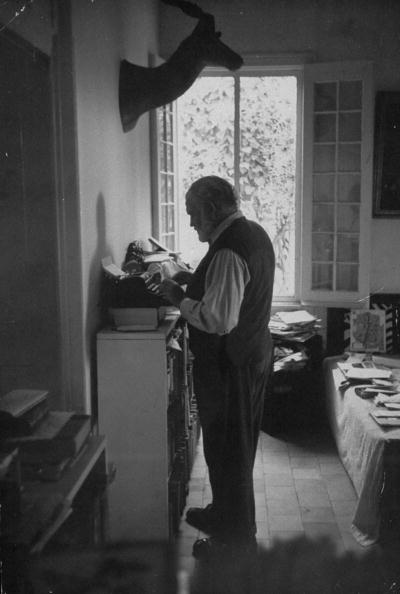

“Nothing could match a writer’s satisfaction in making a new piece of the world and knowing that it would stand forever. Writing was what [Hemingway] had come to earth to do. It was his true faith, his church, his politics, his command.” –Carlos Baker

Though Ernest Hemingway was proficient in a wide variety of skills, there was one area in which he achieved absolute mastery: writing.

It is unusual for a prodigious man of action to also be a brilliant man of words. But Hemingway was both, and treated writing as no less vital, no less arduous, no less epic than any physical contest or battle. It was a serious thing, an almost holy thing; though he loved it, he also considered it “hell.” “It takes it all out of you,” he said, “it nearly kills you.” He referred to his vocation as “the awful responsibility of writing,” and ever felt its weight.

Being a writer was all Hemingway really wanted in life, and it wasn’t enough for him to be simply good, or even great. He wanted to be the best there ever was; with each new work he strove to surpass his last, as well as everything else in the cultural canon. As he said when accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature, to be a writer of any ambition is a lonely, solitary pursuit — single combat:

“For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day. For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that has never been done or that others have tried and failed. Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed. How simple the writing of literature would be if it were only necessary to write in another way what has been well written. It is because we have had such great writers in the past that a writer is driven far out past where he can go, out to where no one can help him.”

Hemingway did not succeed in reaching the pinnacle he describes all at once; rather his mastery was achieved the way it always is — through dedicated time and practice.

After working in high school on both the school’s literary magazine and newspaper, he cut his teeth as a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star. He hit the pavement for stories, studied the paper’s style guide, and pumped his fellow journalists for advice.

As a twentysomething trying to make it as a writer in Paris, he lived leanly, worked diligently on his craft, sent out his stories to publishers, and weathered the many rejections he got in return. He later remembered how painful these setbacks felt at the time:

“every day the rejected manuscripts would come back through the slot in the door of that bare room where I lived over the Montmartre sawmill. They’d fall through the slot onto the wood floor, and clipped to them was that most savage of all reprimands—the printed rejection slip. The rejection slip is very hard to take on an empty stomach and there were times when I’d sit at that old wooden table and read one of those cold slips that had been attached to a story I had loved and worked on very hard and believed in, and I couldn’t help crying.”

Papa persevered though, and even when his first novel became a big success, kept to a very strict writing regimen; rather than waiting for inspiration, he courted it through discipline.

While Hemingway is often thought of as a kind of hard-partying epicurean prince, and could certainly go on some benders, when he was writing, he actually kept to a disciplined daily routine. He woke at five-thirty or six in the morning, and went straight to his work:

“I like to start early before I can be distracted by peoples and events. I’ve seen every sunrise of my life. I rise at first light . . . and I start by rereading and editing everything I have written to the point I left off. That way I go through a book I’m writing several hundred times. Then I go right on, no pissing around, crumbling up paper, pacing, because I always stop at a point where I know precisely what’s going to happen next. So I don’t have to crank up every day.”

Hemingway was quite intense about the initial re-reading process, as he felt “Most writers slough off the toughest but most important part of their trade—editing their stuff, honing it and honing it until it gets an edge like the bullfighter’s estoque, the killing sword. One time my son Patrick brought me a story and asked me to edit it for him. I went over it carefully and changed one word. ‘But, Papa,’ Mousy said, ‘you’ve only changed one word.’ I said, ‘If it’s the right word, that’s a lot.’”

Hemingway did his writing standing up, “to reduce the old belly and because you have more vitality on your feet. Who ever went ten rounds sitting on his ass?”

As he put down new lines of prose, he often left three or more spaces in between words, in order to intentionally slow his pace, and force himself to consider the choice of each individual word. He gave all his attention, all his energy to keeping his output taut, to stripping the lines on the page of any pretentiousness, any falseness — to writing “one true sentence.” And then another.

Hemingway aimed to hit 600-1,000 words a day of the “really good,” and after six or seven hours of intensely focused work, would knock off around lunchtime, feeling absolutely exhausted. He relaxed with a drink and the only activity his “emptied” mind could handle — perusing newspapers and magazines. By late afternoon he began to get his energy back, and would fish and socialize with friends and family. But as Baker observes, “Toward the end of dinner . . . he would begin to withdraw into himself [again], for his mind had turned to the creative problems of the morning, and by the time he went to bed, which was always early when he was working, he knew the people, the events, the places and even some of the dialogue he would encounter the following day.”

The next morning, even on the rare occasions Hemingway broke from his routine and stayed up late, he would get up and do it again. He understood that mastery only emerges from religious consistency: “You have to work every day,” he said. “No matter what has happened the day or night before, get up and bite the nail.”

How Ernest Hemingway Lived the T-Shaped Life, and You Can Too

From the above, we can compile this non-exhaustive list of the components of the horizontal axis of Papa’s “T” — his broad skills, aptitudes, and know-how:

- Listening attentively

- Speaking charmingly

- Fishing

- Hunting

- Cooking wild game

- Map reading

- Navigation

- Racehorse evaluating

- Acquiring broad knowledge of history, flora and fauna, art, wine, etc.

- Speaking multiple languages

- Building wilderness shelters

- Tying flies

- Making bullets

- Preparing game for mounting

- Taking care of equipment

- Building a fire

- Milking a cow

- Fireman-style carrying

- Horseback riding

- Skiing

- Harvesting produce

- Camping

- Backpacking

- Hiking

- Administering first aid

- Displaying courage

- Intelligence gathering

- Team leading

- Patrolling/scouting

- Canoeing

- Boating

- Boxing

- Tennis

- Swimming

- Traveling

And we know well what made up the vertical axis of Hemingway’s T — his area of mastery: writing.

The remaining question then is, how did he do it? How did he get good at so much, and become truly excellent in one discipline?

A few takeaways:

Be curious, observant, and inquisitive. Though Hemingway never went to college, he received a thorough “higher” education simply by remaining curious about the world, and the people who inhabited it. He devoured books. He was interested in people from all walks of life, in hearing their stories, and learning their know-how.

For example, when Hemingway stayed at a dude ranch in Wyoming, he would visit with the few other guests there, but liked to slip away to the bunkhouse to hang out with the real ranch hands. “I always learn something from you men,” he told them. “The dudes have nothing to teach me.”

Have a bias towards action. While Hemingway saw immense value in secondhand learning, he saw no substitute for firsthand experience. He was marked, Baker writes, by “his love for the life of action.” He seldom let a thought go unmaterialized in the world. He seldom let an idea go untested.

For example, when it came to his love for bullfighting, it wasn’t enough to watch the contest and to write about it; he had to participate himself: he got in the ring and took part in amateur bullfights, getting banged up in front of a crowd of 20,000.

For Hemingway, it wasn’t enough to drift or take aimless stabs at things; you really had to go after what you wanted. As he was fond of saying, “Never confuse movement with action.”

Have a set routine. Hemingway understood that mastery isn’t born from fits and starts. It’s something you have to work at every single day. He had nothing but disdain for those who enjoyed the identity of a vocation like writing, but who didn’t embrace the grind of it.

There’s one more tactic that not only allowed Hemingway to do so much in life, but to also get so much enjoyment out of it. But it’s such an important practice, it deserves its own piece. To come.

________________________________________________

Sources:

Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story by Carlos Baker

Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir by A. E. Hotchner

The post Ernest Hemingway as a Case Study in Living the T-Shaped Life appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

(via The Art of Manliness)