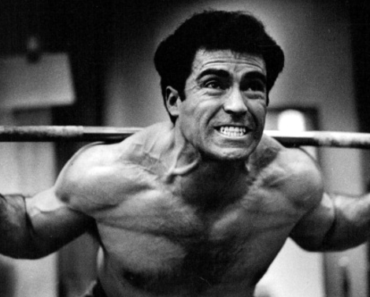

My father wasn’t much of a fisherman. Pitcher, golfer, bowler, woman chaser, fishing was too dull a sport for him. He didn’t have the body or the restraint for it. Born nimble to run and swing and throw, dad wasn’t one to sit beside a lazy stream, powerfully gripping a skinny rod, lying in wait for a bob to jump so he could snag a slimy trout. No, fishing was never his game.

I picture him as a teenager during the bankrupt 30s, playing stickball into the night on the streets of his Italian neighborhood, fiercely defending his team, squashing the opponents. Ignoring his greenhorn father’s commands to stop, to come inside, to do his schoolwork. I hear the complaints in his head, the stubborn silences.

Long after his father’s passing, when the family butcher shop was tenanted by freeloading spiders and their webs, dad and I toured the vacant space. He pointed out a hook on the wall from which hung a long wide strip of rawhide that the old man used to sharpen knives and cleavers. Dad told me that he and his brothers would be whipped across their backsides with the strop when they misbehaved, perhaps explaining why my father used his belt and not the palm of his hand to flog my own brother and me, the leather lashing more business than personal.

At the foot of the stairs, he’d trumpet his warning, “I’m counting.” This meant if we weren’t quiet by the time he reached the number ten, we’d soon find him at our bedroom door. Sometimes we obeyed, more often we were so caught up in the frenzy of our pillow battle that an earthquake could not have muzzled us. “One, two, three…” Likely disturbed in the middle of a favorite television program, he stalled, “I’m taking off my belt.” We persisted. “I’m coming up.” Frozen, we effected a wordless truce and retreated to our twin blonde beds. The ceiling light was switched on and there he stood, strap in hand. The covers were pulled from our bodies, exposing trembling little legs which he thrashed a few times, halfheartedly. To arouse sympathy, we screamed but we stung for no more than a few seconds because as he admitted when we’d grown, “it hurt me more than it hurt you.”

During the Eisenhower 50s and Kennedy 60s, my parents belonged to a social club. They called themselves “The Jolly Jokers.” The group of them, all Italian husbands and wives, mothers and fathers like themselves, came together once a month, each couple taking turns as hosts. The wife would prepare the main course of the meal, the other wives brought the side dishes and the men brought liquor and maybe an extra chair or two. Usually occurring on Saturday evenings, the kids were left with babysitters or the couple’s oldest child of an age capable of being responsible for younger ones. The parents of my cousins, who lived two doors down, were members of the club and so my older sister often babysat six or seven of us at a time in one or the other of our homes. My mother stopped having children after me, the third, but our cousins eventually became a family of eight.

After a huge meal at these raucous get-togethers, plates were cleared and the men crowded around the dinner table to play poker and smoke cigars while the women tidied up and gossiped in the kitchen. We have 16-millimeter film of a New Year’s Eve party where the men compete to see who can strap on a bra and girdle the fastest. You get the idea.

Once or twice a year, the kids would be included. This typically involved a summer picnic at an inner-city park. Fathers and their sons rose very early, before sunrise, and with nets, poles, string and lots of raw bait (everything from fresh chicken parts to hot dogs) caravanned to a distant lake to catch “crawdads.” None of these men was a crawfish specialist and so there were no sophisticated traps, lures or fish bait (which experts will tell you is the best), just what we had laying around the house. It was, after all, meant to be more a prehistoric food hunting, gathering and male bonding experience than a National Geographic expedition.

As adolescents, my brother and I learned more practical lessons from our father (if there can be any more practical than pragmatism and patience): how not to shake hands like a wet fish; how to catch and bat and field a ball; how to change a tire or the oil in a car; to be respectful of clergy, the elderly and women, particularly our mothers; to study and work hard. He assured us that we would be rewarded if we followed the golden rule, but simultaneously counseled that it was okay to defend our position if the other person initiated the attack, did first unto us. As to other pastimes found less than entertaining, he left instruction to others or, as with fishing, he provided the basics and allowed us to discover for ourselves through self-application whether or not the activity suited us.

Lining up our poles and lines, squishy, bloody parts impaled, with nothing to illuminate our prey but the dozing moon, the waking sun, we were drilled that not until a gang of crawfish swarmed around the revolting bait were we to lasso them quickly into our nets before they could get away. Shoulder to shoulder, I caught a heady whiff of dad’s Old Spice, made nauseating when mixed with the polluted mud at my feet. But we pressed on, hungry for our fathers’ affirmations of bravery and machismo as they moved to folding lawn chairs around a raging grill fire, leaving us boy lookouts on the lapping shore between them and the dark and terrifying water in front of us.

Releasing them from their stringy prisons, to which many clung desperately, was the tricky part. “Hold ‘em face down by the centers of their bodies,” dad told me. “That way they can’t nip you with their claws.” Still, their walking legs and reticulated tails put up enough of a ruckus that often I dropped them for fear they could do me irreparable harm. Their antennae alone were cause for alarm, fluttering independently of one another as their bulging, beady eyes seemed also to do. Of course, I never got away without several of them dangling from my fingers which they gripped with all their might.

Whenever he got pinched, or injured in any way for that matter, at least around my brother and sister and me, dad would yelp, “Son of a sea cook.” From the heated way he said it, I knew it to be a vulgar curse, his salty but protective way of not using a more toxic word in front of us kids.

Before I was allowed to join my brother and father on crayfish jaunts, I had seen these crustaceans at our table. (We’d come to love shrimp and crab when we could afford them but this was a decidedly different animal; we’d never seen the others with their heads on.) They were beautiful in their way, ruddy and crumpled peacefully in on themselves like a bowl of red spiral seashells. Of course, we, my siblings and I, wouldn’t touch them, let alone eat them. “These are freshwater lobsters,” dad would embroider. “A delicacy.” Mom seemed not to enjoy them as much but lent her enthusiasm to the endeavor.

Growing up, we’d witnessed the serving and eating of another “delicacy” in our house that similarly made us ill and this was the lowly snail. Our father’s immigrant mother would “purge” them in a pot of salted water – once, even with a lid on, several made their escape into the larger territory of the kitchen – and then she simmered them in a spicy tomato sauce. We dared not watch as dad pried these gentle, innocent beings from their adorable houses and popped the plunder into his mouth lest we have to leave the table to be sick.

His lesson in proper consumption of the crawdad was unforgettable. He’d grab one from its burial mound as if it were a priceless gem plucked from a treasure chest. He’d pull off the tail where the bulk of the meat is found. He’d split open the body and extract the white flesh which does resemble lobster, I have to admit, only so much smaller. Then, he’d wrench off the forelegs that sported the claws and he’d crack these open with his teeth. From the pincers, he would pull more juicy meat, but tinier yet.

If only he’d stopped there. Finally, from the hollow left by the removal of the tail, he sucked out the mustardy, grainy innards from the body cavity, the thorax and head. Well, this was just too much for us. Even mom could not rouse any support. He assured us this wasn’t mandatory. “They’ve been cleaned,” he assured us, though he didn’t say how, and boiling them alive just did not seem enough to us under the circumstances.

So when I caught them for the first time I was surprised to see that they were brownish green and dirty, nothing like the elegant way we came to know them presented at our table.

With each catch, we kept the critters alive in buckets with cold lake water. Once we’d amassed enough to feed ourselves and our mothers and sisters, a couple hundred at least, we soaked them in salted water to give up their dirt. Then we packed them in coolers and headed to the park where we’d later meet “the girls.” By this time, the sun would have risen completely and “the boys” would have had time enough to play a game of softball.

If baiting and catching, cleaning, boiling and eating were all there were to it, I’d be a great fisherman today. And so would a lot of others if it weren’t for the disemboweling. While they’re spinning and writhing, fighting for freedom, claws gouging and tails flapping, “You find the center section of the tail fin, twist it and pull out the intestine.” Who knew the beast had an anus and a digestive tract? If they’d told us it had a heart and soul, that would have been the end of it.

With the dozen or so of us, our fathers and their sons, this process went quickly. And we timed it so that when completed, all that was left to do was toss them, disemboweled but still wriggling, into the boiling pot with spices, corn and potatoes that the women brought and prepared. The crawdads needed only five minutes to cook, exotically beautiful when they were drained and plunked from their pot onto the plastic table-clothed picnic table. The hot bath flushed them, they appeared more glowingly healthy when dead, delightfully edible. The spices imbued them with a gastronomical dignity and the steamy piquant scent floated higher than our spirits, all combining to evoke a Louisiana Cajun country fais-do-do.

My father died at 67 before he got to retire or take mother to the Hawaiian Islands as they’d planned and dreamed. A life cut short. Were it not for him, there’d be many things to fear but trying certainly isn’t one of them. I don’t know how I ended up with it, but the enormous crawdad boiling pot resides in my pantry. I use it only when I host a gathering for a king crab boil. It’s the one pot in which the long legs will fit without breaking at the joints. They have feelings, too, you know, these marvelous creatures of the shallows that my father introduced me to so many lifetimes ago.

Photo: Pixabay

The post Fishing With My Father appeared first on The Good Men Project.

(via The Good Men Project)