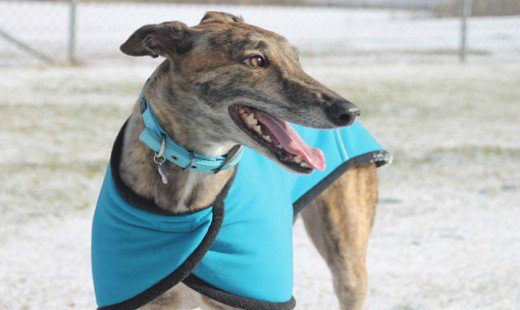

By any measure, Jasper’s got it good, but he hasn’t always led “the life of Riley.”

Like most greyhounds, he was used, abused and discarded by the notorious dog-racing industry. When he was “retired” following a leg injury after just a year of racing, he was severely underweight, riddled with internal parasites and suffering from serious dental neglect. He was terrified of men and is still skittish around them.

Today, Jasper weighs a healthy 90 pounds and lives with my friend and her three cats in a cozy house with a spacious yard in Norfolk, Virginia. He never misses a walk, sees the vet regularly, is best friends with another greyhound, and eats better than I do–he even gets fruit smoothies for breakfast.

Best of all, he has someone who loves him—something that every dog deserves.

The approximately 150 greyhounds who are being held captive in an old shed in Cherokee, Texas, don’t experience anything close to love. Like Jasper, most were treated as commodities by an industry that cares only about profits. But unlike him, they’re still being denied exercise, companionship and the chance to bond with a human family—everything that makes life meaningful to them.

Instead, these graceful, sweet-tempered dogs are routinely abused by another self-serving profiteer: The Pet Blood Bank, Inc., a dog-blood factory farm that sells their blood to veterinary supply companies.

A PETA exposé revealed that the greyhounds are snared with a crude catchpole and put in crates for hours—often while muzzled and without access to water in the blazing-hot Texas sun—before finally being taken into a trailer to be bled. After losing up to 20 percent of their blood volume, many are so weak that they have to be carried back to the squalid, dirt-floored wire cages and the old chemical tanks that serve as their “shelter.” They stay there, usually all alone, until they’re bled again.

Deprived of any enrichment or activity, they chew on the tanks, leaving sharp, jagged edges that can cut and puncture their thin skin. Many of them pace and spin in circles—clear signs of severe psychological distress. Others cry out when approached or are so terrified that they cower and lose control of their bladders or bowels.

Veterinary care for them is nonexistent. The nails of many of these dogs are so overgrown that they curl around into their paw pads, causing them to limp. Many suffer from severe gingivitis and receding gums, which make eating difficult. In a crude attempt to control ticks and other parasites, workers spray the dogs with an insecticide meant for buildings and trees, blistering their skin and irritating their eyes. Two greyhounds, who had no access to water, were found dead in their kennels.

But this blood factory isn’t the only place where “man’s best friend” is being abused and exploited.

About four hours to the east, in College Station, experimenters at Texas A&M University deliberately breed golden retrievers to develop muscular dystrophy. Ravaged by the muscle-wasting disease, they are isolated in barren metal cages and struggle to swallow even thin gruel. These experiments have been going on for more than 30 years and haven’t produced even one effective treatment for the disease in humans.

Across the country, puppy mills—mass-breeding factories that put profits before animal welfare—supply pet stores with animals who are often ill and unsocialized, while millions of dogs languish in animal shelters, waiting to be adopted.

And greyhounds are still forced to run for their lives on racing tracks in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Texas and West Virginia.

It shakes me to the core to imagine my own pups, Max, Danny, and Turk, being abused in these ways. But simply holding them close and wishing that other dogs were treated as well as they are doesn’t cut it, not when we can protest, write letters, sign petitions and attend city council meetings to demand that all dogs get the respect and loving homes that they deserve.

If we don’t, who will?

Photo: Pixabay

The post In Cold Blood: Captive Greyhounds Know Nothing But Suffering appeared first on The Good Men Project.

(via The Good Men Project)