Some parents teach their children how to fish or sew or drive; mine taught me how to roast and carve a chicken. Raised by a mother who cooked almost every night, by whose side I stood when I was young, I absorbed the daily lessons of knives and heat and timing and seasoning. Those who can cook by instinct (rather than instruction) have a confidence that allows them to roam the aisles of the supermarket (or the farmers’ market, or the shelves of their own kitchen, or their imaginations) and take inspiration from whatever strikes their fancy. These cooks can plan and execute a multi-course dinner party on a whim, or look into a nearly empty refrigerator and create a beautiful dish out of odds and ends. I find this calming and pleasurable.

For those who can’t and don’t, lessons are in order. Over the past ten years—and most heavily over the last five—a glut of back-to-basics, technique-focused cookbooks has emerged. They promise to get people into the kitchen with the information they need to make cooking intuitive: the contemporary holy grail of home cooking.

Photo by James Ransom

Some treat cooking more as a spiritual art, like Tamar Adler does in her lyrical book An Everlasting Meal (2012); some, like J. Kenji López-Alt’s The Food Lab (2015) and Michael Ruhlman’s Ratio (2011), more as a science. Some are written narratively, like Cal Peternell’s Twelve Recipes (2014), while others, like The Haven’s Kitchen Cooking School by Alison Cayne (2017), are more explicitly didactic. Some focus on teaching through recipes, as home cook Julia Turshen does in her friendly, accommodating Small Victories (2016); veteran cookbook author Patricia Wells does in her instructional book My Master Recipes (2017); and restaurant chef Naomi Pomeroy rigorously does in her book Taste & Technique (2016). Samin Nosrat’s Salt Fat Acid Heat (2017) takes a combined artistic-scientific-narrative-didactic-recipe-focused approach.

There is much overlap in the recipes and skills presented in these titles. Nearly every book has a tip for dicing onions, instructions on how to salt boiling water, a recipe for mayonnaise, an herby green sauce, a vinaigrette, a pot of beans, a handful of soups and salads, a take on roast chicken or grilled steak, a pastry dough recipe, a cake. Not that this is unusual—this table of contents could be found in any number of contemporary cookbooks filed on a “General Cooking” shelf. What’s notable among these books is the variance in approach to these basics. Individually, each of these authors can teach a person how to boil an egg or braise vegetables; together, their combined voices offer a holistic portrait in what, how, and why to cook.

by Caroline Lange

There are various opinions on why this trend in holistic how-to-cook books is spiking now. New York cookbook seller Bonnie Slotnick cynically chocks it up to capitalism: “Things change in the world of commerce because people have to be lured into spending money,” she says. Then she softens a bit: “These days, more people are writing about food in a personal way, and people respond to that.” Matt Sartwell, the managing partner at Kitchen Arts & Letters in New York, takes a broader view. “Book publishing is pendulum-like,” he says. “Things swing back and forth. One year you’ll have a plethora of glossy, almost stupefyingly beautiful chef showcase books, and the next year everything is about weeknight cooking. And books that focus on technique have had a long tradition in American publishing.”

Indeed, books set on teaching home cooks how to cook at home are not new, and the 1960’s and 70’s saw a dramatic rise in how-to-cook books: Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle (1961), Michael Field’s Cooking School by Michael Field (1965), The Making of a Cook by Madeleine Kamman (1971), Jacques Pepin’s La Technique (1976), James Beard’s Theory & Practice of Good Cooking (1977) were all intended to bring the techniques of classic western European cooking into the American home. For many, the widespread prosperity of this era had led to a new culinary curiosity and experimentation, and books were the primary means of exploration and guidance.

by Sarah Whitman-Salkin

Janice Longone, curator of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the University of Michigan, points to a number of factors contributing to people’s renewed interest in learning to cook mid-century. New kitchen appliances and equipment, a result of economic growth and greater individual purchasing power, got more people into the kitchen—many of whom, according to Longone, “didn’t even know how to open a refrigerator!” Television shows like Julia Child’s 1963 “The French Chef” was a revelation for many; it upped the accessibility of home cooking. Learning to cook “foreign” food took on a fun and hobbyistic quality in a way it never had before.

Today, hobby has transformed into obsession, and food from around the world is widely accessible. Whether people are trying new things in restaurants or getting on a plane or simply launching Instagram, eaters are exposed to far more variety than ever before—a fact that Longone believes has led to a resurgence in an interest in cooking. “When you start traveling,” she says, “you open your mind and eyes and appetites.” Travel-oriented cookbooks that focus on technique are also seeing a rise in popularity, such as those by Naomi Duguid, Fuschia Dunlop, and Shane Mitchell.

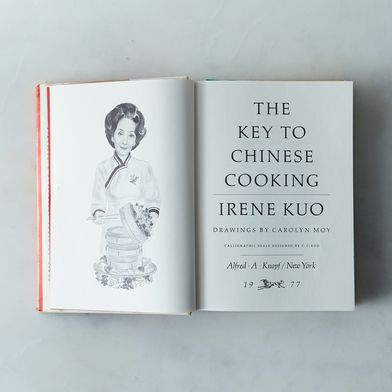

But the cuisines and cooking methods of non-Western cultures were written about throughout the 20th Century—before virtual travel and widespread ingredient access. American home cooks were introduced to new tastes and techniques in books, like A Book of Middle Eastern Food by Claudia Roden (1968), The Cuisines of Mexico by Diana Kennedy (1972), An Invitation to Indian Cooking by Madhur Jaffrey (1973), Couscous and Other Good Food from Morocco by Paula Wolfert (1973), The Home Book of Indonesian Cookery by Sri Owen (1976), The Key to Chinese Cooking by Irene Kuo (1977)—all of which are still indispensable (if out-of-print) resources.

by Mayukh Sen

by Mayukh Sen

by Mayukh Sen

by Mayukh Sen

The flavors and dishes presented in these classic books are no longer novelty, however, and their legacy can be found throughout the pages of this new generation of instructional books: Nosrat offers a recipe for Classic French Herb Salsa (a dissonant phrase, perhaps) as well as recipes for Mexican-ish Herb Salsa, Southeast Asian-ish Herb Salsa, and Japanese-ish Herb Salsa. Peternell varies a traditional Italian meatball with Mexican Meatballs (cumin cilantro, green chilies), Moroccan Meatballs (lamb, cumin, mint), Indian Meatballs (coriander, cardamom, cinnamon), and Syrian Meatballs (paprika, allspice, cumin). Turshen provides a Thai and a Colombian spin-off in her recipe for chicken soup. Miso, lemongrass, tahini, fish sauce, and many other ingredients appear throughout these books’ pages, offering ethnically diverse—if not entirely authentic—variety.

Though today’s technique-focused books are almost exclusively interested in the techniques of western European cooking, many of their recipes reflect the reality that, over time, the basic idea of what a home cook needs (and wants) to know has radically shifted. No longer are elaborate classical skills like boning a duck or whipping up a velouté the norm. Today, people want to cook seasonal, uncomplicated food, and to incorporate a wide range of flavors—not just those from the French tradition. But consumers’ broad tastes have led to a gap between the foods eaters enjoy and the foods they can prepare themselves. “People nowadays are often used to eating better than they know how to cook,” says Matt Sartwell—a fact that, he notes, “makes kitchen failure or experimentation intimidating.”

Obliterating this sense of intimidation is the motivation behind many of these new cookbooks. “As much as we live in this food-obsessed culture, there’s no reason why cooking should be intuitive to you,” says Alison Cayne, the founder of Haven’s Kitchen, a cooking school in Manhattan. “Somehow, in our brains, we think cooking should come very naturally to us. All of that is interfering with getting into the kitchen and having a good time.” Her cohort of authors seems to agree with this sentiment. Each of their books encourages readers to “practice, practice, practice” (Pomeroy) so that “you will get to know some fundamental techniques by heart” (Waters) and “grow comfortable enough to cook without recipes on a daily basis” (Nosrat). But among all these perspectives and approaches and voices, it’s easy for the novice cook to feel overwhelmed, like there is no right way to do things. Tamar Adler acknowledges as much: “I don’t know why we make it so difficult,” she writes. “Perhaps we can’t bear the simplicity of it.”

What I Learned

Though I don’t need to learn how to cut broccoli into florets, I came away from these cookbooks with some valuable lessons.

Understand every action. For those of us who learned to cook by doing (rather than by explicitly being taught), many lessons become intuitive without the knowledge of why we do them. Taking the time to learn why everything needs to be cold when making pastry dough, or why you need a clean bowl to whip egg whites, or why salt makes everything taste better, increases our awareness of our behavior in the kitchen, and makes us better cooks.

Question everything. I learned to cook from my mother, who learned to cook from her mother, who learned to cook from hers. There is great knowledge in generational cooking… but sometimes there are better ways to do things than your great-grandmother did them. Being open to a new technique can lead to delicious new traditions—or radically improve the way you cook, say, meat, as The Food Lab has done for me.

Photo by Issy Croker

The basics are basics for a reason. Once we know how to cook, we naturally feel like the next step should be to cook new and different dishes all the time. These books reminded me of the pleasure of sautéed greens on garlic-rubbed toast (with or without a poached egg on top), or a bowl of polenta covered in black pepper and Parmesan cheese (with or without a poached egg on top). When every basic element is done properly, a dish transcends.

Get the pan hot before adding oil. The first time I read this I brushed it off as one author’s quirky approach to sautéing. Then I read it again in another book. And then again and then again, at which point I realized that I’d been sautéing wrong my entire life. Heating the pan and then adding the oil preserves the flavor of the oil and heats it quickly, so it’s ready to take the rest of your ingredients. It’s never too late to do something right.

The fun never ends. Reading all these books, I was reminded of just how much I really love to cook: to plan a menu, to shop for ingredients, to chop and dice things up, add them to heat, season them so they become something more than the sum of their parts, feed the people I love. These books inspired me to try new dishes, to spend more time exploring what the seasons have to offer, and most of all to cook more. There are an endless number of new recipes to try, new techniques to explore, new ingredients to learn to work with, and new pleasures to discover in the kitchen—no matter your skill level.

(via Food52)